As a child, I was fascinated and horrified by a neighbor lady with freckles covering her face and limbs. As freckles continued forming on my face, my dad would look at me mornings and say, “Debbie, have you grown more freckles?” to which I panicked.

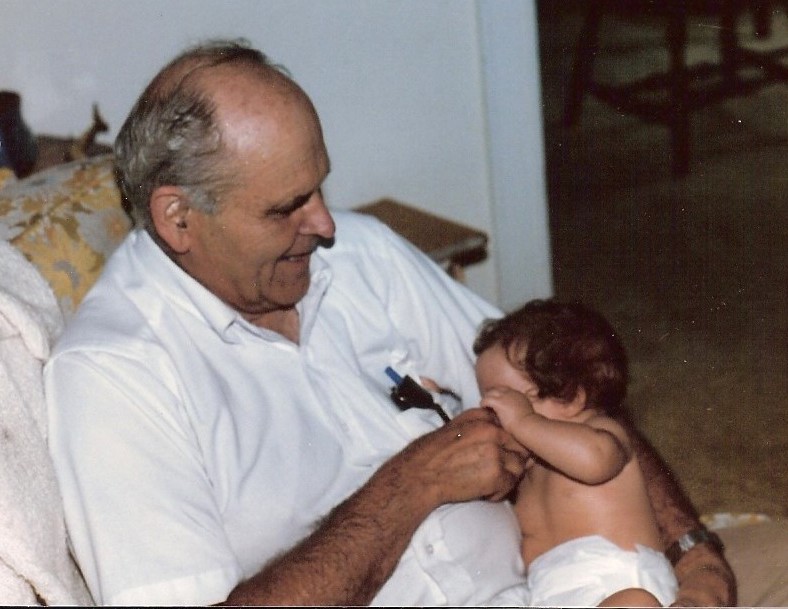

Now I wonder where and how Dad learned to be a dad. He took us on nature walks and played board games like “Uncle Wiggily,” based on an elderly rheumatic rabbit character that debuted as a comic and became a book in 1913. Dad nick-named me Skeezicks, after Uncle Wiggily’s pal, a crow-like being in colorful clothing who, with Uncle Wiggily, played tricks on the other characters.

He would buy complicated puzzles, lay the pieces out on a card table and ask me to help with it. He was color-challenged and would ask me if the colors matched on pieces he was about to fit together. Usually they didn’t so he’d sit back and watch me find ones that did. He taught us “feet fights” which requires lying on your back with knees bent and feet placed on your opponent’s as you tried to push the other’s over an established boundary line. He told bedtime stories about “Itzy Wizzits”, a race of people so thin they disappeared when they turned sideways. As a youth he’d been a vaudeville fan and never lost his fascination for odd entertainment. He’d call us in to watch an Ed Sullivan show featuring a foot juggler or plate spinner who incorporated hardboiled eggs in his act. Dad usually quipped, “That’s talent!” He’d buy recordings of quirky music, like Yma Sumac with her 5-octave vocal range, Gheorghe Zamfir on his pan flute and Los Indios Trabajaras of a north Brazilian tribe, and play them for anyone entering the house, remarking on their unusual abilities.

But how did he learn all this? His parents separated when he was young. His father was eccentric, especially after driving his car off a cliff, cracking his skull and living with a metal plate installed in his head that caused him to receive radio programs. This apparently also hindered his graduation from Harvard. Ironically, he had a career at WABC radio in New York and founded and managed a program called the Negro Achievement Hour (debuted in 1928).

To illustrate my grandfather’s irresponsibility, he sank Dad’s sailboat in New York harbor. To illustrate his mother’s meanness, Dad said she’d thrown a can of tuna at his head when he was about six years old. I heard this story for decades, somehow thinking it was just an empty tuna can which sounded abusive but maybe not heinous at a time when parents routinely beat their kids. When it occurred to me it had been a full can, I asked, “What were you doing that might have caused her to do that?” Without a beat, he replied, “I was sticking a fork into the electrical socket.” “Dad!” I said. “All these years you’ve maligned her but she probably saved your life!”

Like his conversations, Dad’s prose seemed impressionistic. Mom thought it was because he’d skipped grades in school and hadn’t mastered certain lessons. But he had a way with words. I thought he’d be a hit at a Chicago poetry slam but couldn’t convince him. His greatest image was when my parents had moved to a lovely retirement community. Dad likened it to a “cruise ship on the River Styx.” He taught me a lot. He was a wonderful dad.

Have you read SYLVIE DENIED yet? I invite you to grab your copy, and please leave an honest review when you do!

Beautiful. Brought a big smile to my face.

Thanks for saying so, Steve.